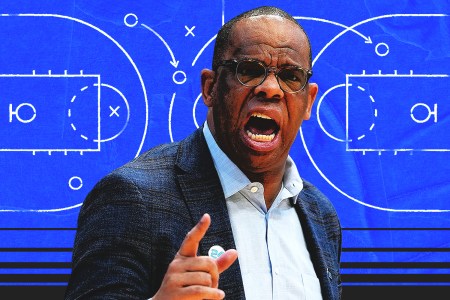

After a summertime practice, Tennessee coach Rick Barnes is chatting with a visitor when he glances over and sees 6-foot-11 senior center Felix Okpara launching jump shots. Most of Okpara’s teammates have departed; the day’s workout has been grueling, ending in a series of suicide sprints, but Okpara, whose scoring repertoire to this point is limited to mostly dunks, wants to develop another weapon and knows he needs extra practice time to do it.

The wheels in Barnes’ brain begin to turn.

The coach calls over Okpara, then asks director of basketball operations Mary-Carter Eggert to get his iPad from his car. After Eggert returns, Barnes opens the tablet, tells Okpara to sit and begins showing him and the visitor clip after clip of NBA big men shooting jumpers with textbook form, the ball in the proper high-release position to make their shots harder for defenders to alter or block.

The impromptu film session ends, and Barnes motions Okpara toward a basket mounted on a side wall of Tennessee’s practice facility. “I’ll be right back,” Barnes tells his guest.

But the visitor knows better. This has happened before. Barnes won’t be back. And that’s OK. The practice floor is his laboratory, the place where he’s committed his long and successful career to helping everyone he’s coached — whether it was Kevin Durant at Texas or a walk-on who might never play a minute — squeeze as much out of their ability as they can. That summer day it was Okpara’s turn, and he must have been paying attention and put in a lot more work on his own. In a late-September conversation with Hoops HQ, Barnes says he is going to encourage Okpara — who has taken 12 three-pointers spread across two seasons at Ohio State and another at Tennessee — to let it fly from behind the arc.

“Coach is so focused on the individual player maximizing their basketball potential,” says Texas general manager Chris Ogden, who has played for and coached alongside Barnes. “Even more so than the winning of championships. Obviously, he wants to win, but he is truly committed to maximizing individual improvement. There aren’t many coaches who do it to that maniacal of a level.”

Ogden laughs at his choice of the word “maniacal,” but it’s appropriate. Barnes has a compulsive need to help his players get better. “Because of what basketball’s done for him,” Ogden says. “Coach grew up on the other side of the tracks. He wants basketball to do for every player what it’s done for him. It changed his life.”

At 71, Barnes’ life in basketball is still in full-speed-ahead mode. By nearly every metric, his 10 seasons at Tennessee have been a rousing success. The Vols haven’t played on “the last Monday night,” as Barnes calls the goal that motivates him every day, but he’s led his last two teams to the Elite Eight and to seven consecutive NCAA Tournaments. Tennessee has won at least 25 games six times in Barnes’ tenure and spent 134 weeks in the Associated Press Top 25 — including 76 in the top 10, 38 in the top five, and nine at No. 1. Since 2017-18, the Vols have won 23 postseason games, tops in the rugged Southeastern Conference. They regularly sell out their 21,678-seat Food City Center. Players graduate. They don’t show up in newspaper headlines for the wrong reasons. Since 2019, 10 Tennessee players have been taken in the NBA Draft. Only Kentucky and Duke can match that number.

Little wonder the Tennessee administration recently signed Barnes to a lifetime contract. “I’m 71,” says Barnes, who spares the needle for no one, not even himself. “So a lifetime contract is not a high risk.”

“Hard on the Body”: Coach Mark Madsen on Cal’s Travel Troubles

Cross-country treks have fatigued the Cal Golden Bears. The ACC’s newest members posted a dismal 1-7 record on Eastern swings last season.

Barnes has always built his programs around player development, but at Tennessee, his work in that critical facet of program-building has come into sharper focus. His second full recruiting class included Grant Williams, an undersized post player whose only college offers were from Ivy League schools. By the time Williams’ career ended after his junior season, he was a two-time SEC Player of the Year. He was picked in the first round of the 2019 NBA Draft by the Boston Celtics and has also played for Dallas and Charlotte. In September, he made a $1.5 million donation to Tennessee, $750,000 of it earmarked for the men’s basketball Excellence Fund.

In the NIL/transfer portal era, Barnes and his staff have developed a reputation for finding talented mid-major players and turning them into Draft picks. In 2023-24, Dalton Knecht came from Northern Colorado, led the SEC in scoring, was chosen as the league’s Player of the Year and earned the Julius Erving Small Forward of the Year award. He was selected by the Lakers in the first round of the 2023 Draft.

Last season, Chaz Lanier, a native Tennessean, returned home from North Florida, led the Vols in scoring, broke former Tennessee star Chris Lofton’s single-season record for made three-pointers (123) and was voted the Jerry West Shooting Guard of the Year. He was drafted last June and signed a four-year deal with the Detroit Pistons.

Who will be the Dalton Knecht or Chaz Lanier on Barnes’ 2025-26 team, which he calls the deepest he has coached at Tennessee? Before we go there, it’s telling to trace the origins of Barnes’ penchant for helping his players achieve their dreams. It began in the ‘60s, when Barnes was a small but scrappy player at North Carolina’s Hickory High School. In those days, playing basketball in the summer was almost unheard of, but Barnes made regular trips to the Hickory Foundation Center, where he practiced on his own but, more importantly, often watched Hickory’s star player Dave Miller — who went on to play at NC State — work out.

“I’d rebound for him as he shot,” Barnes says. “When he got done, I’d try to emulate what he did. He was always in the gym. Because of him, I learned the importance of working on the game year-round.”

During one of his daily workouts, Barnes met John Lentz, who played for Lenoir-Rhyne University, also located in Hickory.

“Dad was watching Rick shoot around,” says Bryan Lentz, who has worked on Barnes’ staff at Texas and for the last eight years at Tennessee. “He said, ‘Rick, what are you doing?’ Rick said he was trying to get better. Dad said, ‘You have no idea what you’re doing. If you want to work, you have to know exactly what you’re doing.’”

With that, Barnes’ mindset about game improvement was born. “John was all about player development,” Barnes says. “He would always tell me that John Wooden quote, ‘Don’t mistake activity for achievement.’”

Barnes improved his game to the point he was able to join John Lentz at Lenoir-Rhyne, where the latter, after a record-breaking playing career, coached for 29 years. Barnes and Lentz never coached together or against one another, but when the time came to repay one of his earliest mentors, Barnes hired his son. It’s no surprise Bryan Lentz’s first job title at Tennessee was director of player development.

From George Mason, his first-head coaching job, to Providence, Clemson, Texas and Tennessee, Barnes has never forgotten what he learned from his hometown heroes. “Every kid dreams of playing basketball in the big leagues,” Barnes says. “They don’t realize how hard it is to get there.”

Barnes is happy to remind them. He’s notoriously hard on his players in practice, often stopping the proceedings to reinforce a point — at high volume. When yelling doesn’t work, Barnes will banish a player to run the steps at Food City Center, or if the Vols are working in their practice facility, he might make the whole team run sprints.

Though he’s demanding and unrelenting on the court — “He sees everything,” says associate head coach Justin Gainey, “every little mistake” — off the court Barnes is a father figure.

Hubert Davis Isn’t Concerned About Pressure

Expectations are high at North Carolina. Hubert Davis fully embraces it.

“Those two things go hand in hand,” says junior forward Cade Phillips, who could well be Barnes’ latest success story as he moves from center, where he was sometimes forced to play last season, to small forward. “Being hard on us is extracting the best from us. It’s a fine line [Barnes] has to walk where his players can grow but not be pushed too hard where they can’t come back up. That’s what’s made him as successful as he’s been for as long as he has.”

Barnes is equally invested in the careers of his assistants. Three who have worked for him at Tennessee are now head coaches: Rob Lanier (Rice), Kim English (Providence) and Michael Schwartz (East Carolina). Assistants are immersed in every facet of the program, from taking charge of practices to standing in for Barnes at press conferences. When head-coaching opportunities arise, the assistants are ready, and Barnes practically pushes them out the door — sad to see them go but elated that they, too, are getting a chance to live their dreams.

This season, Barnes — ninth on the all-time Division I wins list and first among active coaches (836) — has a team capable of another deep NCAA Tournament run. In 2025-25, he led a group of just nine scholarship players, only seven of whom played major minutes, to the Elite Eight. The Vols’ didn’t have a low-post scoring threat, and their only consistent three-point shooter was Lanier.

Now, after regaining the services of 6-foot-11 sophomore J.P. Estella, who missed most of last season with a foot injury, and adding former Vanderbilt player Jaylen Carey and freshman DeWayne Brown II — “The biggest surprise of the summer; not even close,” Barnes says — to go along with an improved Okpara, the Vols will have a rugged and deep post rotation that can score at the rim, offensive rebound and block shots.

On the perimeter, scoring threats are plentiful. Five-star freshman Nate Ament could play all five positions, but the 6-foot-10 future lottery pick will wind up at shooting guard or small forward. “He’s everything we thought he would be, and much, much, much more,” Barnes says. Point guard Ja’Kobi Gillespie, another native Tennessean who returned home after playing two seasons at Belmont and another at Maryland, has already drawn the attention of NBA scouts. He’s a knockdown three-point shooter, a crafty passer and every bit the defensive threat former Vol great Zakai Zeigler, who graduated after last season, was.

Ogden sizes up Tennessee’s roster, and it reminds him of some of Barnes’ best teams. “When coach has had a real point guard, a lottery pick and rebounding, his teams have won big,” Ogden says.

In late September, Barnes wasn’t sure about his starting lineup, but if he wanted to, he could play Ament at the two and Phillips at the three, giving him four starters 6-foot-9 or taller. His guard corps, bolstered by the summertime additions of international players Clarence Massamba (France) and Ethan Burg (Israel), is so deep Barnes will expand his rotation to 10 or 11 players, meaning the Vols can exert themselves on defense — a hallmark of Barnes-coached teams — and still have fresh legs on the offensive end.

“I love this team,” Barnes says. “We’ve got a long way to go, but we’ve got great camaraderie and work ethic. These kids all want to get better. And that’s why you do it. Money has obviously become part of the equation, but if you would ask any of the older coaches, they didn’t get into this for the money. They got into it because they love the game, and because they love to help these young guys maximize their talent, at whatever level that might eventually be.”